A lot has happened to the plague doctor since Chinese rats hitchhiked with exotic trade goods to Europe in the 14th century. The beak - which long contained oils, herbs and rose petals - is now filled with organic black tea from the fabled Yunnan province in China.

With rats from China

It was probably a flea-infested gang of rats that brought the bubonic plague to Europe. They are thought to have been stowaways on the camel caravans carrying trade goods from China. History's worst plague epidemic, the Black Death, was an unintended part of the trade as exotic goods such as spices, silk and gold were transported along the fabled Silk Road. At the centre of the thankless job of fighting the epidemic, which reduced the world's population by 150 million in about 50 years, was the plague doctor.

There was little the plague doctor could do about the bubonic plague. They were far better at counting dead bodies than curing them, and often had the task of logging deaths. The plague doctor's main function was to act as a witness in connection with wills and other important documents relating to plague victims. The risks associated with the job, combined with the desperate mood that prevailed in Europe, made plague doctors sought after and highly pressurised. They were usually hired by the authorities of countries or cities, and were therefore just as likely to visit the poor as the rich. Nevertheless, many took advantage of the opportunity to demand money directly from the families of those infected. The other side of the coin was the almost inevitable fate of the plague doctor, who was himself a victim of the plague.

Counterproductive

Although the plague doctor played a role as early as the Black Death in the 14th century, it was centuries before the mythical costume saw the light of day. It was the French physician Charles de l'Orme (1584-1678) who breathed life into the costume, which has since become a source of inspiration for a long line of writers, storytellers and film makers. The purpose of the costume was to protect himself from the heavily afflicted plague victims he visited, and its morbid appearance was born out of the cruel and deadly nature of the plague epidemics. Although the costume is believed to have been counterproductive, spreading infection rather than protecting, it worked satisfactorily for l'Orme, who lived to be 96. For a doctor in plague-stricken 17th century France, that's quite an achievement.

The costume from hat to leather boots

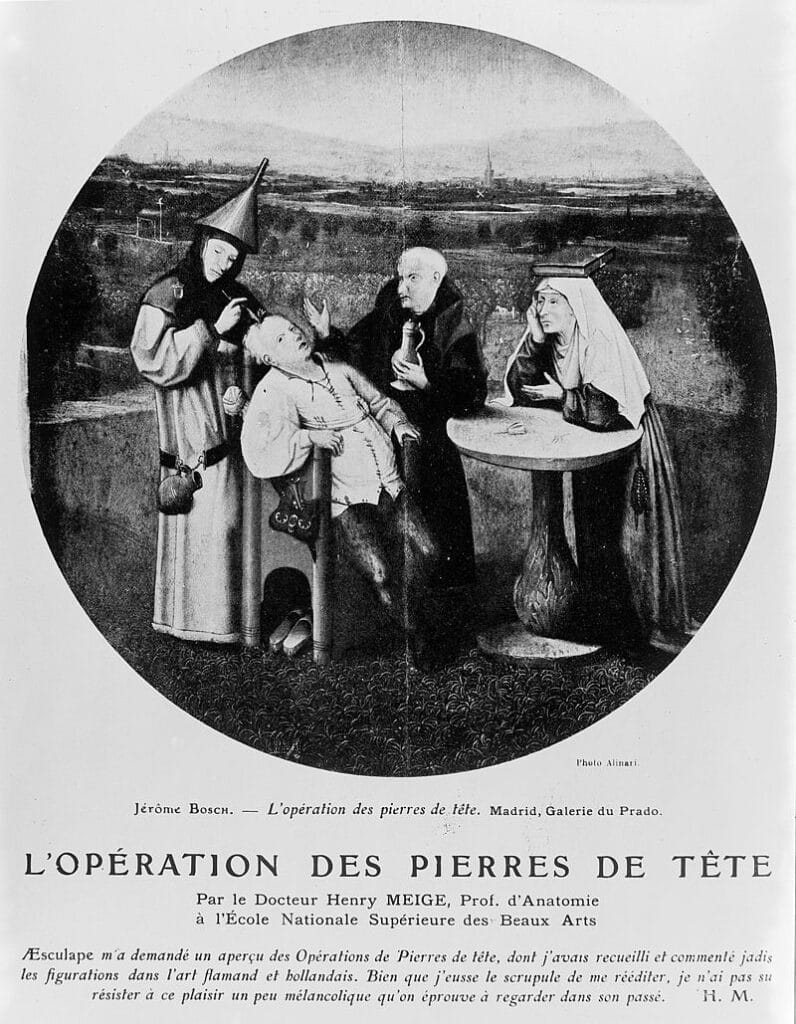

The postdoctoral researcher wore a wide-brimmed black hat that was pulled tightly down over his head. The beaked mask was hollow and filled with strong-smelling oils, spices and rose petals to mask the odour of death and unburied corpses. In the mask's large, soulless eye sockets, red pieces of glass were placed to keep evil out. On his body, the plague doctor wore a full-length black suit covered in thick wax. Under the coat, leather knee breeches were attached to high leather boots to protect the groin, which was often the first area of the body to be attacked.

When the plague doctor adorns our Black Tea today, it is wrapped in several layers of symbolic value. The black tea inside is a Chinese import with the opposite sign of the 14th century bubonic plague. While the original plague doctor's curved beak contained oils, herbs and rose petals, our version is filled exclusively with pure black tea with hints of golden shoots. Today, the dark Middle Ages are only a distant memory for the plague doctor, who has a far more pleasant task in life: To fill as many cups as he can with top-quality organic black tea.